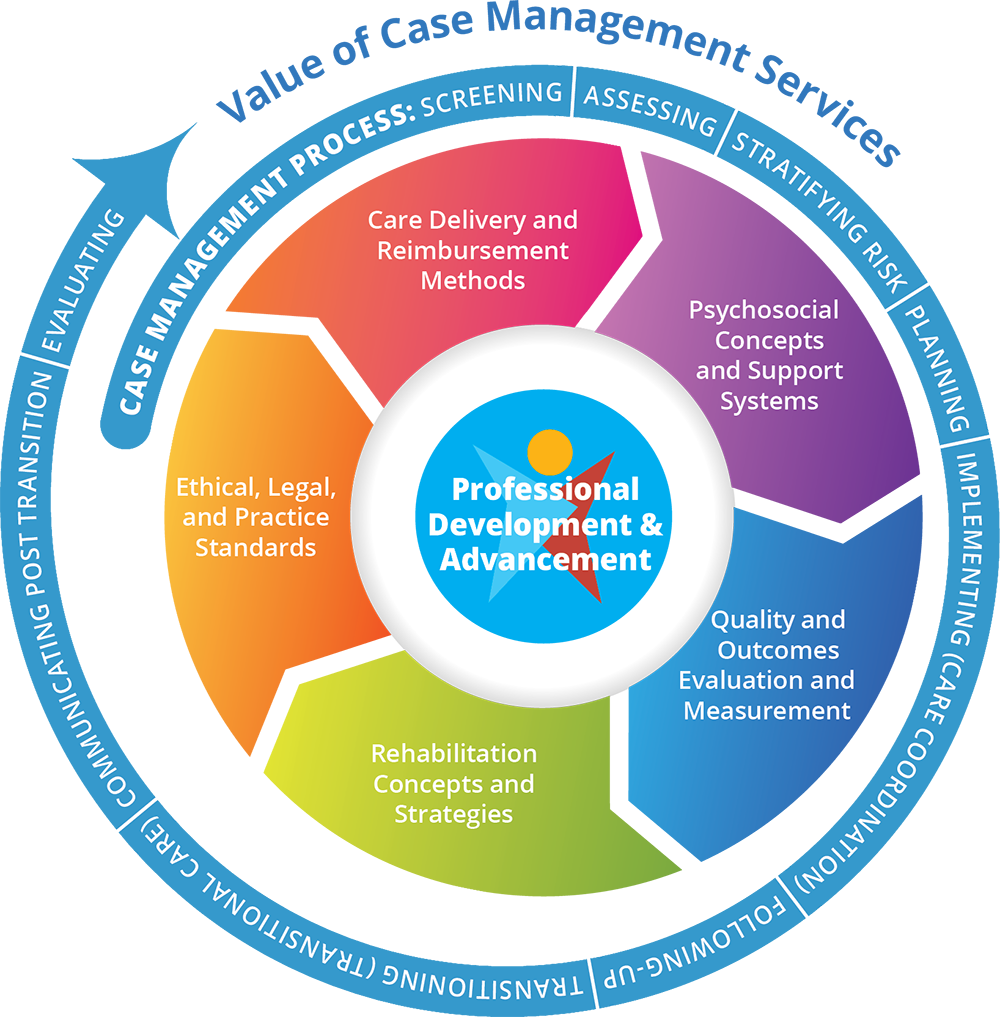

The Scope of Practice section of the Code asserts that case management is guided by five ethical principles (2015, p. 3). These are fundamental and deserve your closest attention.

- Autonomy

- Beneficence

- Nonmaleficence

- Justice

- Veracity

These principles have been popularized by ethics scholars Tom Beauchamp and James Childress in their book Principles of Biomedical Ethics (2009). This book has been enormously influential in shaping the contemporary nature of bioethical conversations and analyses – primarily by way of its painstaking and thoughtful analyses and discussions.

Beauchamp and Childress spend many pages of their book showing how the principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice play out in healthcare practice and how these terms can specifically apply to case management practice.

Autonomy

The term autonomy is taken from two Greek words, auto and nomos, which literally mean “self-rule.” In Western liberal countries – and in the United States particularly – autonomy is a cherished concept. The language of autonomy resonates with the language of:

- Independence

- Liberty

- Individual rights

- Self-determination

Autonomy is at the heart of American citizens’ cultural identity; honoring it means that you respect one another’s choices, decisions, and behaviors, as long as they are lawful and don’t pose an unreasonable risk of injury to the individual or to others.

Nevertheless, honoring autonomy can be difficult for at least two reasons.

Two Key Challenges Case Managers Face in Honoring Autonomy

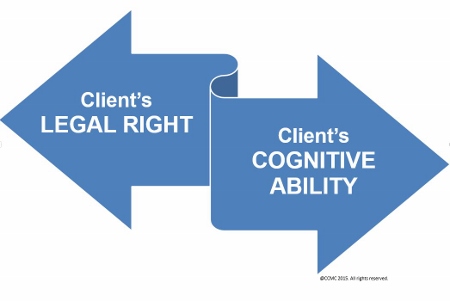

First, although the client has a legal right to behave in a particular way, it may be difficult for you in your duties as case manager to honor this right if you believe the individual is acting foolishly or irrationally.

Second, in order to authentically exert autonomy, an individual must have the cognitive ability to understand, reason about, and appreciate the nature and likely consequences of his/her behavior.

Suppose you are confronted by a client whose health behaviors are exceedingly poor. Despite your instructions and exhortations, the client continues to eat an unhealthy diet and engages in all kinds of health risks that sabotage your efforts. How are you supposed to honor this individual’s autonomy?

Once you realize that your efforts are failing to help this client, you may call on a nutritionist or maybe a psychologist who can set up a behavioral health program. But if the client continues to staunchly reject these efforts, or fails to comply with them yet appears to understand the consequences of his doing so, it is clear that:

- The client’s resistance is an authentic expression of autonomy;

- You have done what you can reasonably do and are professionally obligated to do; and

- You are ethically justified in severing your professional relationship with this client because the latter is simply not living up to his part of the case management agreement.

The right of autonomy includes a right to make risky or hazardous decisions – as long as those decisions do not unreasonably imperil oneself or others, and clients understand and accept the risks they are assuming from their ill-advised choices and decisions.

An important aspect of autonomy is that it is affected by the client’s cognitive ability and its impact on the consequences of his/her behavior.

An important aspect of autonomy is that it is affected by the client’s cognitive ability and its impact on the consequences of his/her behavior.

Consider the case in which your client is poorly educated, cannot pay attention long enough to absorb your instructions, cannot read above a second grade level, or suffers symptoms of early dementia.

Or perhaps the client is severely depressed: his conversation is coherent and on point, but his decisions nevertheless reflect a profound gloom and disinterest in getting well and an intractable expectation that things will only get worse.

You, the case manager, have a duty to protect the client from himself and others.

You, the case manager, have a duty to protect the client from himself and others.

What are you to do in such situations? How do you honor these clients’ autonomy? You may:

- Use your motivational interviewing skills to see if you can get to the real issues and concerns your client is facing and address them.

- Continue to educate your client about his/her condition, offering interventions and services available to ultimately arrive at an option your client agrees to pursue.

- Involve a member of the client’s support system in the discussion, with the client’s consent – perhaps a member of the client’s choosing.

- Highlight potentially favorable outcomes of the suggested interventions and services.

- Discuss your client’s situation with other members of the interdisciplinary healthcare team to create a plan together.

Consider now another client whose situation has worsened – suppose he becomes suicidal and communicates his suicidal ideations to you – and you have taken no supportive measures whatsoever. You might rightfully be accused of incompetence bordering on abandonment.

Example of Autonomy and Change in a Client’s Condition

| Case Scenario | Commentary |

|---|---|

| All would probably agree that a case manager who becomes aware that her client’s driving skills have deteriorated to the point at which he constitutes a hazard has a professional obligation to call this to some authority’s attention, such as the client’s physician. |

If none of the client’s health professionals take reasonable steps to remedy this situation – and if the client does indeed harm someone in a driving incident – those health professionals can certainly be blamed for their unresponsiveness, and they can be sued in some states for failure to protect third parties.

Taking steps that culminate in the revocation of someone’s driving privileges can be an extremely unpleasant undertaking and can also result in the professional’s losing that individual as a client. Driving an automobile, living by oneself, raising children according to one’s values, bearing arms, and engaging in intimate relationships are hallmark examples of a citizen’s self-determinative autonomous rights. When rights such as those are abbreviated or revoked, persons might react with deep feelings of anger and even vengefulness toward those who were trying to help. |

When you are caring for clients who are unable to exert autonomy (e.g., clients who lack judgmental capacity or who – if they have been so adjudicated by the courts – are “incompetent”) you must ensure that you are coordinating your clients’ care with whomever is legally authorized to do so.

Usually, this person is a next of kin, a designated healthcare proxy, or a court-appointed guardian often identified in state law as the one authorized to make medical and healthcare decisions on the client’s behalf.

Because the majority of case managers are trained in either nursing, social work, or vocational rehabilitation, they should be aware of the need to proceed only with case management plans of care for their clients that have been already approved by the client’s lawfully designated surrogate or proxy.

Because the majority of case managers are trained in either nursing, social work, or vocational rehabilitation, they should be aware of the need to proceed only with case management plans of care for their clients that have been already approved by the client’s lawfully designated surrogate or proxy.

Whenever you are confronted with challenging situations in your case management role, you should seek advice from reliable sources that inform what a “reasonable and prudent” case manager would do.

“Reasonable and prudent” are the measures the law expects from any healthcare professional confronted with similar conditions. These are the measures courts use to assess professional case management behavior.

“Reasonable and prudent” are the measures the law expects from any healthcare professional confronted with similar conditions. These are the measures courts use to assess professional case management behavior.

A court rarely imposes its own notion of what counts as reasonable and prudent in a particular case. Instead, the courts will put the question to the case manager’s peers or to court-appointed experts. Thus, if you recognize that your behavior is clearly unorthodox and would not be supported by your peers, you are probably skating on very thin ethical and professional ice.

Case managers must note the congruence rather than dissonance between ethics and law.

Case managers must note the congruence rather than dissonance between ethics and law.

Reasonable and prudent behaviors are not only good criteria for meeting legal expectations, they usually meet ethical expectations as well. Professionals are not obligated to meet their clients’ needs endlessly, but they are obligated to meet what case management ethical standards expect. (This includes an adherence to the law.)

In matters relating to problematic client behaviors or decisions, you might be one of the first to notice them but perhaps not know what to do – unless you are appropriately trained in this regard (e.g., behavioral health, ethics).

Case managers should have access to procedures and resources for the care of clients whose behavior seems significantly problematic and dangerous rather than just eccentric. These might be legal or social service resources, clinical programs, or consultants who can give professional advice or care.

Case managers should have access to procedures and resources for the care of clients whose behavior seems significantly problematic and dangerous rather than just eccentric. These might be legal or social service resources, clinical programs, or consultants who can give professional advice or care.

To the extent that clients are reasonably autonomous, they bear the responsibility for their decisions. However, once the clients’ cognitive faculties fail them – and they can no longer exercise autonomy because they cannot adequately understand, reason about, exert adequate insight, or appreciate the consequences of their decisions – their healthcare professionals or their surrogates become responsible for them and what happens to them.

Case managers need to be acutely aware of the impact of the client’s cognitive condition on autonomy, and be able to take appropriate steps to protect both their client’s and their own welfare.

Case managers need to be acutely aware of the impact of the client’s cognitive condition on autonomy, and be able to take appropriate steps to protect both their client’s and their own welfare.

Nonmaleficence

Nonmaleficence means refraining from harming others, as in the common phrase, “above all, do no harm.”

To refrain from harming is, of course, the most basic expectation that any health consumer will have of his/her health provider, while health professionals are probably appalled at the very idea that a professional would intentionally harm a client.

Unfortunately, both instances of intentional as well as unintentional harm occur often in healthcare.

Unfortunately, both instances of intentional as well as unintentional harm occur often in healthcare.

Because case management involves an elaborate array of services that occur in “a professional and collaborate process that assesses, plans, implements, coordinates, monitors, and evaluates the options and services required to meet an individual’s health needs” (CCMC, 2015, p. 4), you are extremely vulnerable to any number of situations that can challenge your ethical skill set.

Consider how clients can be harmed by your failing to comply with the relevant CCMC standards as described in the Code of Professional Conduct for Case Managers.

Ethical Standards and Board-Certified Case Managers

|

Case Management Actions Demonstrating Adherence to Ethical Standards |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compiled based on the CCMC Code of Professional Conduct for Case Managers with Standards, Rules, Procedures, and Penalties by the Commission for Case Manager Certification, January 2015, Mount Laurel, NJ: CCMC.

This lengthy list of possible harms – when adherence to ethical standards is lacking – speaks to the sheer volume of ethical responsibilities you assume as case manager.

All case managers should be somewhat knowledgeable about many of the ethical standards above. For example, a case manager who does not know anything about confidentiality and privacy requirements, criminal behavior, informed consent, and ordinary professional courtesy would be seriously lacking in essential information, and therefore would potentially act in ways that violate the Code.

A particularly trying situation that invites maleficent behavior is when you become exasperated with or even come to dislike a particular client/support system. In a situation such as this, the possibility of harming a client becomes quite real. Your natural reaction is often to be rid of this person. Although understandable, this feeling can translate itself into any number of problematic behaviors on your part such as:

- Ignoring the client’s/support system’s questions

- Lecturing, sermonizing, arguing, or blaming

- Feeling a strong aversion to communicating at all with the client/support system

These behaviors would hardly be conducive to a respectful, productive, or professional relationship between you and the client/support system and – ultimately – good case management outcomes.

It is easy to hear advice to remain emotionally calm and objective in situations of disempowering feelings (e.g., anger, resentment), behaviors (e.g., ignoring, lecturing) or thoughts (e.g., desire not to interact with the client). However, that advice can prove extremely difficult to realize among clients who are controlling, overly critical and demanding, angry, manipulative, provocative, ornery, impossible to please, or threatening.

Because it often feels like these kinds of clients are on the attack – and they often are because they might be venting their anger and frustration at the case manager – the case manager might feel a natural inclination to act defensively.

Because it often feels like these kinds of clients are on the attack – and they often are because they might be venting their anger and frustration at the case manager – the case manager might feel a natural inclination to act defensively.

Often you may find that the easiest way to remain emotionally calm and objective is by distancing yourself from challenging clients. This does a disservice to these clients. Such behaviors are against ethical case management practice standards.

Because these kinds of situations that risk a maleficent response from you can easily occur, you must possess empathy to some degree.

Empathic communication techniques can prove enormously valuable in disempowering feelings, thoughts, or behaviors triggered by the client’s situation.

Empathic communication techniques can prove enormously valuable in disempowering feelings, thoughts, or behaviors triggered by the client’s situation.

Regardless of how you are actually feeling at any given moment, your ability to respond in a supportive, nonjudgmental, and compassionate manner to the challenging client/support system can be invaluable. This is not hypocritical. A case manager – like any healthcare professional – should be exercising skills aimed at the client’s empowerment and improvement.

For example, if you express your true feelings toward your client/support system (e.g., exasperation and even dislike of the client), and those feelings turn out to be maladaptive toward reaching a therapeutic goal, then such expression cannot have clinical value, no matter how authentically it reflects your feelings or state of mind.

Empathic Phrases and Responses

| Examples of Empathic Phrases and Responses |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: For more information on empathic interaction, see “ ‘Let Me See If I Have This Right…’: Words That Help Build Empathy” by John L. Coulehan, Frederic W. Platt, Barry Egener, Richard Frankel, Chen-Tan Lin, Beth Lown, & William H. Salazar, 2001, Annals of Internal Medicine, 135(3), pp. 221-227. Copyright 2001 by American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. Doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-3-200108070-00022 and/or “SPIKES—A Six-Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient with Cancer” by Walter F. Baile, Robert Buckman, Renato Lenzi, Gary Glober, Estela A. Beale, & Andrzej P. Kudelka, 2000, The Oncologist, Volume 5, pp. 302-311. Copyright by AlphaMed Press. Doi:10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302

Your first obligation – as for any healthcare professional – is to put the client’s needs first rather than your need to express relief of psychological or emotional discomfort.

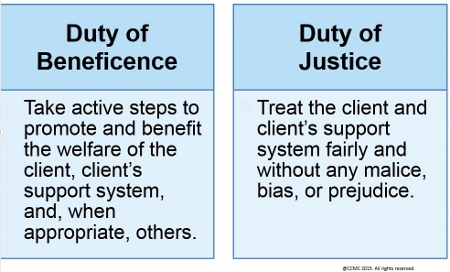

Beneficence and Justice

In case management practice, you demonstrate just treatment through the ethical allocation of benefits to your clients/support systems.

Duty of Beneficence and Justice

Consider pondering the following questions daily:

- How do you determine what counts as a “benefit” for your client?

- What if you, your client, and the third-party payor disagree on the value of a particular benefit?

- How much benefit do you owe your clients?

- How do you evaluate the quality of a benefit when, in certain situations, not all benefits can be offered?

- What if you are simply unable to effect the allocation of a particularly desirable benefit?

These questions contribute to ethical dilemmas and sometimes frustration. You should not become defensive when clients/support systems view your professional activities as focused more on cutting costs or limiting their care. The simple fact that case management is an instrument in reducing healthcare expenditures is, at face value, ethically laudable. Whatever can be ethically done to reduce healthcare expenses is a good thing indeed.

Particularly challenging – especially in case management contexts – is the clash when a client appears to need a benefit but his/her coverage will not reimburse it.

Particularly challenging – especially in case management contexts – is the clash when a client appears to need a benefit but his/her coverage will not reimburse it.

Clashes between clients’ benefits and needs frequently play out in terms of a conflict between need versus ability to pay. The clash can be heart rending, especially in pediatric cases or cases involving clients whose very lives might seem to depend on a desperate – perhaps improbable – surgery or experimental treatment. Thus:

- Should you advocate for your client to receive an experimental treatment that is very expensive and whose success probability has not been determined?

- What about certain treatments that might deliver a benefit but only for a short duration, such as allocating heroic treatments that will prolong the lives of clients who are nevertheless terminally ill?

- Do you allocate such treatments despite their costs if they prolong life but do not provide a decent quality of life? And who is to judge when a life has “decent” quality?

Furthermore, whatever counts as a duty, a benefit, or even virtuous behavior varies among clients and healthcare professionals, such that you can never remove those cultural factors that are increasingly complicating healthcare decision making.

Many case managers are confronted daily with clients from diverse cultures whose expectations and beliefs about their health and their healthcare may be at considerable odds with Western practices and assumptions.

Many case managers are confronted daily with clients from diverse cultures whose expectations and beliefs about their health and their healthcare may be at considerable odds with Western practices and assumptions.

Prior to the era of managed care, healthcare professionals in the West had enormous latitude to impose their values on what counts as a client benefit. This was an age of paternalism, in which the values of the medical establishment went unquestioned, clients/support systems did as they were told, physicians ordered whatever treatments they considered beneficial, and third-party payors reimbursed those costs, usually without a whimper.

With the emergence of extraordinary medical technologies such as artificial ventilation, dialysis, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, improved and safer anesthesia, and designer antibiotics, healthcare budgets soared and became economically unsustainable. Managed care – or something like it – had to happen simply to maintain a lid on healthcare spending. Of course, a primary challenge was to set and maintain that lid ethically.

Case management occurs in such a context: one of high ethical aspirations that aim at superior healthcare outcomes, but that also recognize that the reservoir of benefits is not bottomless.

Case management occurs in such a context: one of high ethical aspirations that aim at superior healthcare outcomes, but that also recognize that the reservoir of benefits is not bottomless.

The solution that American healthcare devised in the last 30 years is to evolve a system whose benefits allocation would not rest on an ethical vision of goodness, duty, or welfare, but rather on a contract – that is, an insurance policy. (For more about this, see Insurance Policies and Contractual Ethics.)

Veracity

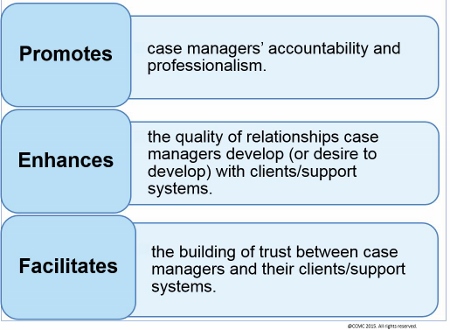

Veracity is the ethical principle that obligates you to tell the truth to your clients/support systems, professional colleagues, and any other individual or entity you deal with while providing case management services. Truth telling adds value both to you as case manager and to your clients/support systems.

Three Main Benefits of Veracity (Truth Telling)

If you violate the ethical principle of veracity, you lose your credibility with – and the respect of – your clients and fellow professional colleagues.

You adhere to veracity when you:

- Communicate honestly

- Share relevant, accurate, clear, and understandable information

- Conform to the facts

- Remain objective

- Practice habitual truthfulness

Veracity is grounded in respecting the client’s autonomy and right to self-determination. You may enhance veracity through fidelity – which requires loyalty, fairness, advocacy, integrity, and dedication to your clients/support systems.

To develop trusting relationships with clients/support systems, you must demonstrate faithfulness, truthfulness, honesty, transparency, sincerity, and fidelity.

To develop trusting relationships with clients/support systems, you must demonstrate faithfulness, truthfulness, honesty, transparency, sincerity, and fidelity.

Some clients/support systems may verbalize their desire not to know the full truth or all the details of their condition and prognosis. Clients may also ask that their support system not be informed of their diagnosis or prognosis. In these cases, case managers must respect the wishes of the clients/support systems. Withholding information in these cases does not mean case managers have violated the ethical principle of veracity.

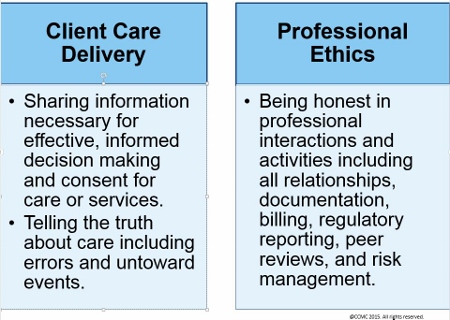

Veracity is most applicable in two main aspects of client care delivery and case management practice.

Two Broad Applications of Veracity in Case Management

You can prevent violating the ethical principle of veracity by avoiding:

- The act of lying or the deliberate exchange of erroneous information

- Omission or withholding of part or all of the truth

- Use of medical jargon that misleads clients/support systems or results in lack of understanding of the situation

Insurance Policies and Contractual Ethics

It would be marvelous to discover an ethical template that would resolve moral dilemmas – a template somewhat like Newton’s laws of physics, Euclid’s theorems, or the periodic table of the chemical elements.

Unlike the laws that govern the physical universe, what occurs in the “moral universe” does not appear to be regulated by the kind of timeless principles that physical scientists discover.

Unlike the laws that govern the physical universe, what occurs in the “moral universe” does not appear to be regulated by the kind of timeless principles that physical scientists discover.

A strong argument can be made that ethical principles like autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, veracity, and justice become refined in their meanings and application through a process of trial and error requiring centuries of debate, mistakes, and – inevitably throughout history – wars and major political movements.

Put another way, cultures, societies, and civilizations do not begin with highly sophisticated ideas of freedom, welfare, and justice. Instead, over time they encounter problem after problem and develop institutions like legislatures, religions, professional societies, and centers of learning (e.g., colleges and universities) that study and recommend what these principles should ultimately mean and how they should be applied in human practice.

For thousands of years the practice of ethics has been evolving; each civilization has influenced changes in ethical standards. The most recent decade is no exception, where use of innovative therapies and healthcare and social media technologies have presented us with complex ethical problems. These are mostly attributed to scientific and technology progress in numerous areas including, among others, genetics, synthetic biology, nanotechnology, neuroscience, electronic medical records, and Internet-based communication media. You, the case manager, must remain aware of these innovations and their ethical implications.

Because ethical theory cannot explicitly advise the case manager on whether or not to advocate for an experimental intervention for her client or at what point the client’s treatment becomes “futile,” the case manager must use her ethical reasoning and judgment to search for an answer.

Because ethical theory cannot explicitly advise the case manager on whether or not to advocate for an experimental intervention for her client or at what point the client’s treatment becomes “futile,” the case manager must use her ethical reasoning and judgment to search for an answer.

Even when you exercise ethical reasoning and judgment, your views can differ significantly from those of other case managers on their perceptions of what is ethically at stake, what ethical principles can mean, and how they should be applied in a given case. Because the stakes are so economically high in many of these cases, the financial costs of your ethical decisions must be taken into account. If they aren’t, then the very system that allows for the allocation of healthcare benefits could collapse.

Health Insurance Policies

In its actuarial way, the health insurance policy (contract) cuts through the thicket of difficult ethical decisions by enumerating what benefits your client is “owed.” Because it is a contractual agreement in which the contractors each get something they want and because – it is to be hoped – neither party is being unduly manipulated or coerced into entering into the contract, the acceptance of the terms is understood to be mutual, voluntary, and consensual.

One of the practical functions of a health insurance policy is to control the financial costs of the relationship between a health insurance purchaser (who is also the healthcare consumer), healthcare providers, and reimbursement sources.

One of the practical functions of a health insurance policy is to control the financial costs of the relationship between a health insurance purchaser (who is also the healthcare consumer), healthcare providers, and reimbursement sources.

You may consider the health insurance policy (contract) to be:

- An ethical instrument. In other words, because it is vexing and contentious to arrive at some universal conception of “benefit” and “justice,” the health insurance contract is an attempt to settle these complex matters at the level of a buyer and seller of services.

- A marketplace solution to problems that would frequently present as imponderable if you tried to resolve them at a philosophical level. Instead, you refer them to the parties who are directly involved, and you decide to honor their freely willed and considered decisions as to whether to proceed into the arrangement and the terms outlined in the policy.

Consequently, to the extent that the health insurance policy is precisely detailed with benefits, exclusions, and descriptions as to how disputes are to be settled, philosophical determinations of the “right” or “good” have been replaced by a marketplace, consumer-driven purchasing arrangement.

Notice also how ingeniously a contractual marketplace solution to health benefits can respond if it is accused of failing to offer appropriate goods or benefits. The response can simply be that all potential insurance buyers are free to look around for the best policy.

Assuming a robustly competitive insurance marketplace exists, the potential buyer (i.e., client) can ultimately settle on a policy with the best benefits at the best price. If he/she is dissatisfied with the available purchasing options, then as long as no one is forcing him/her to buy, the arrangement does not appear ethically vile.|

Despite the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, not every uninsured person has signed on for health insurance using the insurance exchanges. It might, of course, be far from ethically ideal if persons who have not signed on and purchased a health insurance policy from these exchanges, and at the same time cannot afford to pay for healthcare, face the threat of personal bankruptcy if they develop a long and expensive-to-treat illness.

But among persons who can afford to pay and who enjoy a robustly competitive health insurance marketplace – in which vendors are fiercely competing against one another to offer the best services at the best price – the contractual solution to answering “Who gets what and how much?” has evolved as a provocative solution to overcoming what are essentially very deep and vexing ethical questions, especially as they occur in morally pluralistic societies.

Adhesion Contracts

None of the previous discussion implies that insurers and the health insurance marketplace can do no wrong. Further, it is likely that insurers at times:

- Misrepresent their services or knowingly promise more than they deliver.

- Refuse to reimburse a product or service to which an insured is clearly entitled.

- Force an insured to go through an arduous appeals process in order to get what is rightfully theirs.

- Provide a service but at an inferior level of quality or delivered by unqualified individuals.

- Insist that the insured pay for costs that were concealed when the contract was executed.

- Resist adjudicating disputes according to the process outlined in the insurance policy.

Each of these wrongs seems to involve some form of fraud and – to the extent it does – it is ethically reprehensible. But to the extent that there is an honest dispute over insurance coverage, ethics might have very little to say beyond what a reasonable construal of the policy would provide.

Not surprisingly, when such disputes actually occur, they usually don’t end up before ethics committees, but instead before an administrative law judge who provides a reasonable interpretation of the insurance policy. In this regard, it is important to point out that health insurance policies are usually understood as “adhesion” contracts.

Adhesion contracts are often called “take it or leave it” contracts because one party draws up the contract’s terms and simply presents them to another party.

Adhesion contracts are often called “take it or leave it” contracts because one party draws up the contract’s terms and simply presents them to another party.

Unlike contracts to buy or sell a home, which are usually negotiated back and forth and thus revised numerous times, the terms of an adhesion contract are set by the insurance company or payor and simply handed over to the client on a “take it or leave it” basis.

Nevertheless, when there is a dispute over the terms of an adhesion

contract and the dispute goes to court, the judicial policy is to give the benefit of the doubt to the client.

In other words, if a client could persuade a judge that a reasonable person could construe his/her health policy’s language to say X, the judge should favor the client because the insurer had ample time and opportunity to make the policy as clear as possible.

According to legal reasoning, because the insurer had the advantage of drawing up the policy – and hence the time and opportunity to phrase and stipulate its terms – then any penalty for unclear or ambiguous language relevant to benefits should go against the insurer.

The consumption of healthcare services by those who possess a health insurance plan in the United States focuses on the contents of the insurance policies that are bought and sold in the insurance marketplace. This is a testimony to the failure of ethical theory in areas such as:

- Persuading a nation that access to healthcare services is a basic human good similar to access to clean air and water or to police protection.

- Describing a reasonable scope of healthcare benefits to which everyone should be entitled by right.

The moral pluralism of the United States, in contrast to the moral solidarity of industrialized European nations on universal healthcare access, resulted in over 47 million Americans without healthcare insurance. Although today this number has been declining as a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 where currently over 10 million of these uninsured Americans have purchased insurance policies from the health insurance exchanges.

Consequently, it was a tremendous historical moment when in March 2010 the Obama Administration passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which aims to provide insurance for up to 97 percent of all Americans. Despite efforts to challenge this act, it is alive as of this writing and the number of uninsured Americans has been declining.

The client advocacy of case managers will continue to be informed by the contents of their clients’ insurance coverage, which will likewise continue to inform the question of what case managers “owe” their clients.

The client advocacy of case managers will continue to be informed by the contents of their clients’ insurance coverage, which will likewise continue to inform the question of what case managers “owe” their clients.

Next page: The Case Manager’s Ethical Decision Making

Warning: Cannot modify header information - headers already sent by (output started at /home/cmbok/public_html/includes/common.inc:2791) in /home/cmbok/public_html/includes/bootstrap.inc on line 1499